The Right to Housing in Action

Transforming housing law and policy in Canada

by Sahar Raza, Michèle Biss, Kaitlin Schwan, and Bruce Porter

The National Housing Strategy Act commits the federal government to the realization of the right to adequate housing under international human rights law and puts in place novel mechanisms through which this right is to be realized through a new “rights-based approach.” This is the first legislation of its kind to implement the federal government’s commitment to the realization of a socio-economic right under international law, with important implications in a wide range of law and policy.

In October 2021, the National Right to Housing Network and Women’s National Housing and Homelessness Network released a set of three research reports on what this historic legislation means and how it should be applied. These papers, commissioned by the Office of the Federal Housing Advocate, offer concrete recommendations on how federal government agencies can implement a rights-based approach to housing, so as to both support and benefit from the new accountability mechanisms under the legislation and contribute to the realization of the right to housing in Canada. The papers are entitled:

- Implementing the Right to Adequate Housing Under the National Housing Strategy Act: The International Human Rights Framework by Bruce Porter

- Implementing the Right to Housing in Canada: Expanding the National Housing Strategy by Michèle Biss and Sahar Raza

- Implementation of the Right to Housing for Women, Girls, and Gender Diverse People in Canada by Kaitlin Schwan, Mary-Elizabeth Vaccaro, Luke Reid, and Nadia Ali

DOWNLOAD THE PAPERS HERE (EN FRANÇAIS ICI):

Here’s what you need to know

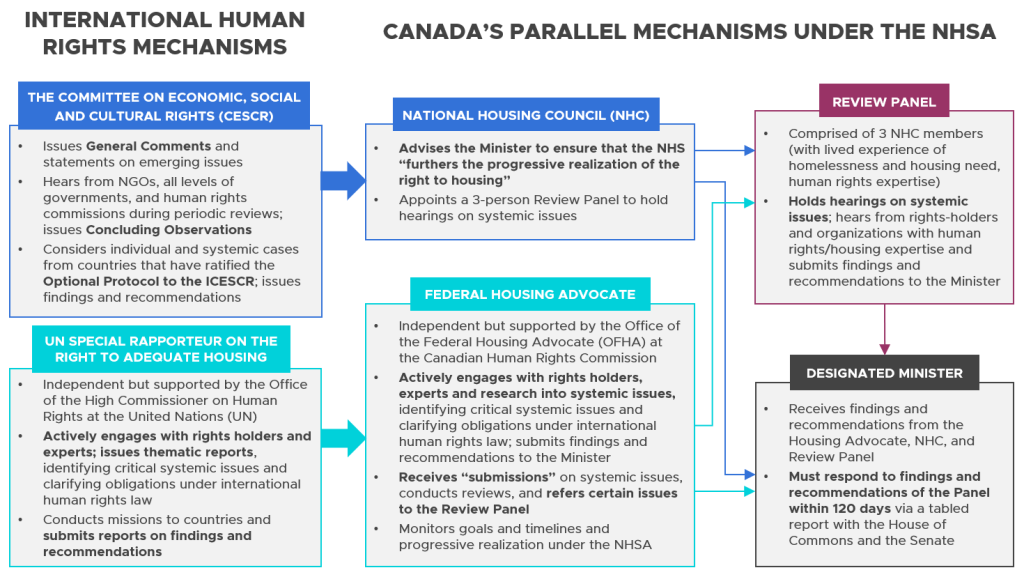

Canada has had international obligations to uphold economic, social, and cultural rights like the right to adequate housing for decades—but accountability to these obligations has relied on remote UN mechanisms and hearings in Geneva. UN human rights bodies have repeatedly urged Canada to recognize the right to housing in legislation and adopt a rights-based national housing strategy with goals and timelines, hearings, and mechanisms to address systemic issues.

The National Housing Strategy Act responds to these recommendations. It requires the Government of Canada to maintain a National Housing Strategy consistent with the right to housing and establishes a number of robust mechanisms to ensure government accountability and community engagement. Two years before, in 2017, Canada had introduced a National Housing Strategy (i.e. “the Strategy”, or the NHS), which referenced Canada’s international human rights commitments to the “right to housing”—but the NHSA goes much further. It explicitly recognizes the right to housing under international human rights law as “a fundamental human right” in legislation. The commitments of the NHSA to the right to housing are a big deal because they open the door to a new era of rights-based housing laws and policies in Canada.

In the 2021 federal election, Canada’s housing and homelessness systems drew significant attention in the media and election discourse. The reality is undeniable—Canada has a devastating housing crisis. This crisis has deepened in recent years, with many government departments working against a tide of financialization, increased rates of homelessness and housing need linked to COVID-19, loss of existing affordable housing, and lack of adequate investment in affordable housing.

The NHSA recognizes that housing is essential for “the dignity and well-being of the person.” It demands that the housing crisis be addressed as a human rights crisis. That means policies and programs must be redesigned to effect serious and transformative change—the kind of change that can only be achieved when we stop allowing a powerful real estate sector to dominate housing policy. The rights-based approach adopted by the NHSA focuses on the people who are actually living in housing need or experiencing homelessness (i.e. rights-claimants), and ensures that they are able to bring to the government’s attention the systemic issues that deny them adequate housing and have their needs addressed. The NHSA reaches back to Canada’s core human rights commitments to redefine housing policy so that it is not just about buildings but about inclusive communities and commitments to equal dignity and rights.

The NHSA recognizes that housing is essential for “the dignity and well-being of the person.” It demands that the housing crisis be addressed as a human rights crisis. That means policies and programs must be redesigned to effect serious and transformative change—the kind of change that can only be achieved when we stop allowing a powerful real estate sector to dominate housing policy. The rights-based approach adopted by the NHSA focuses on the people who are actually living in housing need or experiencing homelessness (i.e. rights-claimants), and ensures that they are able to bring to the government’s attention the systemic issues that deny them adequate housing and have their needs addressed. The NHSA reaches back to Canada’s core human rights commitments to redefine housing policy so that it is not just about buildings but about inclusive communities and commitments to equal dignity and rights.

The novel infrastructure created through the National Housing Strategy Act does not rely on courts for hearings or remedies to the systemic issues that must be addressed. Instead, it uses a “dialogic approach” which is much less adversarial and final than a court case. It allows for rights-claimants to bring forward “systemic issues” (i.e. the big barriers that are driving Canada’s housing crisis). In this system, rights-claimants are involved in a participatory and ever-evolving process where their rights are consistently valued and their voices are amplified—and they play a central part in developing recommendations to change Canada’s housing system.

Basically, this gives an opportunity for rights claimants to directly engage with government departments in a way that challenges existing power dynamics, such that claimants can come up with solutions that directly affect them.

Practically, this dialogic system is dependent on a Federal Housing Advocate who will receive and review systemic claims, adopt findings, and make recommendations to the Minister of Families, Children, and Social Development, who must respond in 120 days. The Federal Housing Advocate also has a unique opportunity to refer cases to a Review Panel, made up of 3 members of the National Housing Council, who will hold open hearings on systemic cases. Recommendations from Review Panel hearings will also go to the Minister, who again must respond within 120 days, but via a tabled response in the House of Commons and the Senate.

For more details on the substantive context of the right to housing and transformative nature of the National Housing Strategy Act, check out Bruce Porter’s paper entitled, “Implementing the Right to Adequate Housing Under the National Housing Strategy Act: The International Human Rights Framework.”

Where does the right to housing come from?

It’s important to remember that the right to housing in not an abstract concept, nor does it mean that the government has an obligation to buy everyone in Canada a house. Just like every other human right (like the right to freedom of expression, the right to life, or the right to equality), there is a whole legal framework grounding the right to housing that international authorities like the United Nations have explored and written about for decades.

The National Housing Strategy Act specifically refers to the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (which Canada ratified in 1976) and commits to the “progressive realization of the right to housing” under that Covenant. With these commitments come international standards like a requirement that Canada commit a “maximum of available resources” and “all appropriate means” to ending homelessness and realizing the right to adequate housing, including through the “adoption of legislative measures.” This needs to be applied alongside Canada’s other human rights obligations, for example with regards to respecting, protecting, and fulfilling the distinct human rights of Indigenous Peoples as articulated in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and realizing the right of persons with disabilities to housing with necessary supports (so as to be fully included in the community).

The National Housing Strategy Act specifically refers to the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (which Canada ratified in 1976) and commits to the “progressive realization of the right to housing” under that Covenant. With these commitments come international standards like a requirement that Canada commit a “maximum of available resources” and “all appropriate means” to ending homelessness and realizing the right to adequate housing, including through the “adoption of legislative measures.” This needs to be applied alongside Canada’s other human rights obligations, for example with regards to respecting, protecting, and fulfilling the distinct human rights of Indigenous Peoples as articulated in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and realizing the right of persons with disabilities to housing with necessary supports (so as to be fully included in the community).

The Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (the independent UN body that reviews Canada and other countries’ compliance with the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights every 5 years) has provided concrete advice on what this means in action. For example, they have said that governments have an obligation to prevent evictions by addressing affordability and other systemic factors, and they must also ensure wherever possible that evictions do not lead to homelessness.

Importantly, in the context of homelessness, Canada has an obligation to adopt targets and timelines for the reduction and elimination of homelessness within the shortest possible amount of time. This means that we also need mechanisms to address systemic barriers to adequate housing, such as: discrimination, inequitable investments in housing in the North, lack of taxation measures to curb the financialization of housing, and lack of funding for housing that truly affordable to those most in need. That’s also part of the Canadian government’s commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals (some may know these as the SDG), in which we promised to eliminate homelessness by 2030.

In assessing whether governments have met their obligation to progressively realize the right to housing, the UN has applied a standard of “reasonableness.” The reasonableness standard encourages us to ask questions like:

- Have government departments engaged with people affected to develop solutions to systemic housing issues?

- Has a horizontal, cross-department approach been adopted?

- Has the federal government exercised leadership to ensure that all levels of government are cooperating to implement their shared human rights obligations with respect to the right to adequate housing?

- Are programs and policies consistent with a commitment to realize the right to housing for all, in the shortest possible time?

The question of what constitutes reasonable policy from a human rights standpoint starts by considering the dignity and rights of those who need housing, and from there, considering whether the government’s response to their circumstances is reasonable and proportional. It is a similar process as has been applied under human rights legislation with respect to the accommodation of disabilities. First, we must hear from rights-holders about what they need from the government to ensure dignity and rights, and then we must consider how to address those needs as human rights priorities, within available resources. This new human rights approach can cast a very different light on our assessment of whether housing policies and programs are “reasonable”—and it also leads to innovative and creative solutions which often result in longer term cost-savings.

But what does this mean in practice? How will this actually change people’s lives?

Alongside the new rights-claiming mechanisms in the NHSA, the Act also creates a requirement that housing policies (and especially the 2017 National Housing Strategy mentioned earlier) are consistent with the right to housing. United Nations authorities have been encouraging Canada to establish a rights-based housing strategy for decades and have also developed criteria for what a genuine rights-based housing strategy looks like and means.

In their paper “Implementing the Right to Housing in Canada: Expanding the National Housing Strategy Act,” authors Michèle Biss and Sahar Raza break down the elements of a rights-based housing strategy as outlined in international human rights law—and offer an analysis of Canada’s current National Housing Strategy (NHS) according to these international standards. This analysis finds that:

- Investments in the NHS are inadequate to meet the goals of reducing core housing need or ending homelessness;

- The NHS is not improving housing outcomes for those most in need; and

- There are few opportunities for people with lived and living experience of homelessness and inadequate housing to participate in the development of the NHS.

Moreover, this paper finds that many critiques of the NHS from rights-claimants, civil society, and academic experts are directly tied to its lack of a rights-based approach. For example, Canada’s inadequate investments in low-income housing can be tied to Canada’s failure to meet the standards of reasonableness and a maximum of available resources. Canada’s housing data can also be better disaggregated to ensure that programmatic housing efforts support those most in need, and to make sure that resources are available for rights-claimants to bring forward systemic claims (in accordance with Canada’s human rights obligations to provide access to justice).

Concretely, this paper weaves recommendations from civil society with international human rights guidelines and standards to recommend that Canada take rights-based actions such as:

- Ensuring that indicators or “core housing need” are refined to address other important dimensions of the right to housing such as cultural adequacy and security of tenure, and that capital and other investments in the National Housing Strategy are consistent with the obligation to reduce core housing need and eliminate homelessness based on agreed timelines;

- Creating measures through the Strategy to address the financialization of housing and the erosion of naturally existing affordable housing. This includes concrete actions and financial policies that prevent large corporate investors and financial actors like Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) from further exploiting the housing market;

- Reframing NHS policies to address the needs of populations who have otherwise been excluded from CMHC’s list of priority populations. This includes specific measures to address inadequate housing and homelessness among those who have interacted with the criminal justice system; persons with precarious immigration status; persons with disabilities who require both housing and accompanying support services to live independently in the community; migrant workers; low-income women and lone caregivers; and rural and remote communities;

- Ensuring that rights-holders are integrated into NHS program design, monitoring, and evaluation; and,

- Working with provinces and territories to ensure compliance with the cross-jurisdictional housing agreements that require provincial/territorial action plans that “complement the NHS goal of helping advance the progressive realization of Canada’s obligations in relation to housing under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).”

For further analysis, check out this assessment of the 2017 National Housing Strategy according to the ten elements of a rights-based housing strategy as outlined by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing.

What does this mean for specific marginalized groups like women and gender-diverse persons?

The right to housing applies to marginalized groups in distinctive ways, just as experiences of Canada’s housing crisis are distinctive. A rights-based approach focuses on those bearing the brunt of Canada’s housing crisis—for example persons with disabilities, persons of colour, and Indigenous persons.

In the Canadian context, women, girls, and gender diverse peoples are one such group, with research indicating that many live in insecure or unsafe housing due to inequity and discrimination. There is a severe lack of affordable and appropriate housing that meets the needs of diverse women and women-led families in Canada, and these groups experience disproportionate levels of core housing need and poverty. Many remain trapped in poverty or in situations of hidden homelessness, putting them at risk of exploitation and abuse while also rendering their needs invisible to mainstream supports, systems, and policy development. The result is widespread violations of the right to housing that are profoundly gendered.

In the Canadian context, women, girls, and gender diverse peoples are one such group, with research indicating that many live in insecure or unsafe housing due to inequity and discrimination. There is a severe lack of affordable and appropriate housing that meets the needs of diverse women and women-led families in Canada, and these groups experience disproportionate levels of core housing need and poverty. Many remain trapped in poverty or in situations of hidden homelessness, putting them at risk of exploitation and abuse while also rendering their needs invisible to mainstream supports, systems, and policy development. The result is widespread violations of the right to housing that are profoundly gendered.

In the paper “Implementation of the Right to Housing for Women, Girls, and Gender Diverse People in Canada“ by Kaitlin Schwan, Mary-Elizabeth Vaccaro, Luke Reid, and Nadia Ali, the authors explore how gender-based inequities within four National Housing Strategy programs are inconsistent with the right to housing. For example, Reaching Home (the primary NHS program aimed at reducing homelessness) has sought to prioritize addressing chronic homelessness in its programs, and the 2020 Speech from the Throne committed the federal government to ending chronic homelessness in Canada. However, the definition of chronic homelessness employed by Reaching Home has been critiqued for failing to account for the ways in which women experience homelessness. This failure contributes to inequitable investments for women who are homeless and severe gaps in supports, services, and emergency housing. As such, the effect of the current definition of chronic homelessness contravenes the government’s obligation to guarantee substantive equality and non-discrimination in the area of housing.

Similarly, the paper notes that the National Housing Co-Investment Fund does not articulate clear targets, timelines, or indicators for its impact on women and gender diverse peoples, including groups that are experiencing intersectional discrimination and the most severe forms of housing instability in Canada (e.g., refugee women-led families fleeing violence). This prevents ongoing monitoring of progress on the realization of the right to housing for these groups, and makes it difficult to assess whether the NHS is reaching its overall goal of ensuring that 25% of its resources are dedicated to women and girls.

So, what’s next?

As a new federal government forms, there are incredible opportunities to use the National Housing Strategy Act to transform our housing systems. Some government agencies have already made much progress in applying lenses like a gender based plus analysis to their policy development and delivery. The rights-based approach outlined in the NHSA provides a new framework to complement GBA+ and expand our focus to the distinct human rights of those living in core housing need and homelessness.

The National Housing Strategy Act provides us a roadmap for realizing the right to housing in Canada, and a framework for transforming our broken housing and homelessness systems. It provides an avenue for a more progressive, participatory, and effective approach to a wide range of policy and programming, and a new approach to governance, based on shared commitments to fundamental human rights.

For more information about making the right to housing a reality, check out the papers:

Implementing the Right to Adequate Housing Under the National Housing Strategy Act: The International Human Rights Framework by Bruce Porter

Canada has both international and domestic obligations to realize the right to housing. This paper details Canada’s legal obligations and offers international human rights principles, norms, and guidelines that Canada can draw from in order to realize the right to housing.

Implementing the Right to Housing in Canada: Expanding the National Housing Strategy by Michèle Biss and Sahar Raza

Affordable housing is eroding at a faster rate than it’s being produced, and Canada’s housing policies and programs are not reaching people in greatest housing need. This paper assesses Canada’s leading housing policy—the National Housing Strategy—through a rights-based lens to reveal its gaps and offer recommendations for improvement using human rights standards.

Implementation of the Right to Housing for Women, Girls, and Gender Diverse People in Canada by Kaitlin Schwan, Mary-Elizabeth Vaccaro, Luke Reid, and Nadia Ali

Already marginalized groups like Indigenous peoples, persons with disabilities, people of colour, Black people, youth, women, immigrants, refugees, gender-diverse persons, seniors, and persons on fixed incomes bear the brunt of the housing crisis. This paper offers a case study on how already-marginalized groups like women, girls and gender diverse persons are uniquely impacted by the housing crisis, and how we can better address their needs using a rights-based approach.